I enjoy Apple products and I’ve got a few, including two Apple TVs. I’m not big on smart-TV stuff, so I only use it for Netflix, YouTube, and some “running around the world” workout videos I keep on my NAS. I know I don’t use Apple TV to its full capabilities—no games, no apps (beyond the above)—and that’s OK by me. I was happy to give Apple my money; their stuff never let me down, and I enjoyed the experience.

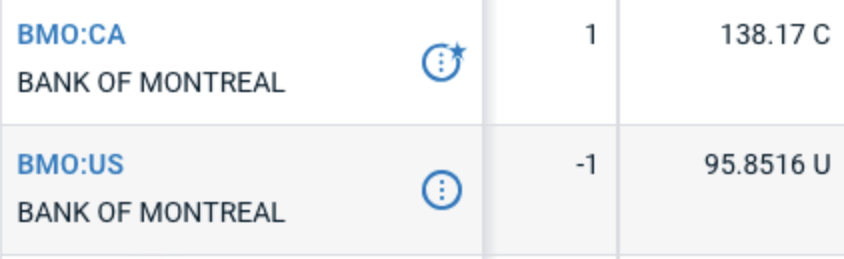

However, this year I was forced to reevaluate my choice. It started when the Apple TV remote battery began to die—it didn’t hold a charge and needed constant recharging. I figured it wasn’t a big deal; I could just change the battery and carry on. Then came the surprise: modern Apple remotes are sealed, and the battery is irreplaceable. I was shocked and disappointed. Maybe it was only that model, I thought; maybe the newer one is different. The new remote looked different—the trackpad is gone and it looks beefier—but it kept the same brain-twisting “feature”: an irreplaceable battery. Even if you’re ready to hack and solder, you can’t buy a replacement battery. Why?

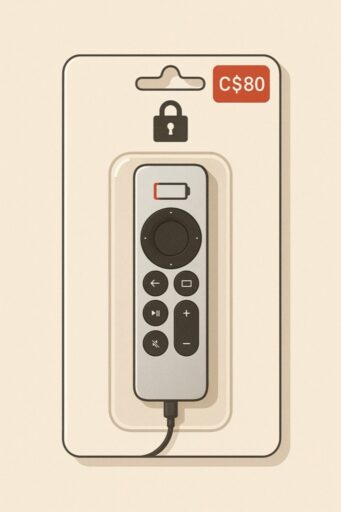

In the old Apple remotes you could always replace the battery, but I guess in this new age of disposable stuff you should just buy a new one. OK, well, let’s buy a new remote… except it isn’t $30–$40; it’s a whopping $80 Canadian. Why? A new Apple TV is $180! So nearly half the cost of the Apple TV is the remote? Really? And the cherry on top: there are no third-party options that work decently.

Everyone knows TV remotes don’t get dropped, smudged, or soaked in breakfast cereal! So yeah, good on Apple for noticing this potential revenue stream and deciding to nickel-and-dime their customers. “Think Different” takes on a new meaning. I mean, it’s a TV remote! Just for comparison: for $80 Canadian you can buy the top model of the Amazon Fire TV Stick—and if you wait for a sale, you can get it down to $50. By the way, the Fire TV remote has the same features—buttons, microphone, Bluetooth—and somehow it all runs on two AAA replaceable batteries! I really didn’t mind giving Apple two or three times more money for Apple TV, but not for an unrepairable, disposable, expensive TV remote.

My journey with Apple TV is coming to an end. I’ve already replaced one, and I’m seriously considering replacing the other as well. Maybe it’s an overreaction, but I can’t help feeling cheated. There’s a lingering distaste I can’t seem to shake off — it just sits there, quietly dulling any reason to look back.