Another year has passed and here I am trying to figure out: was it “better” or “worse”, at least from where I’m sitting. On one hand, the past year could have been a lot worse, but I’m not sure what it says when you start looking at things from a “could have been worse” perspective. Yet another thought ripples through my mind asking: “Does it matter? What are we comparing exactly?”

From a certain point in life, expectations start to diminish as more pressing, close and personal issues occur more often, and the effects can be felt directly. Perhaps it is too early to think and talk about those things, but it is inevitable… well, at least with the current level of technology. I guess we’re gonna get there eventually. If none of this makes sense – it does, since I gave up on the idea of coherent thought today. Just for one day I can let my mind drift and write torn-out thoughts as they float along.

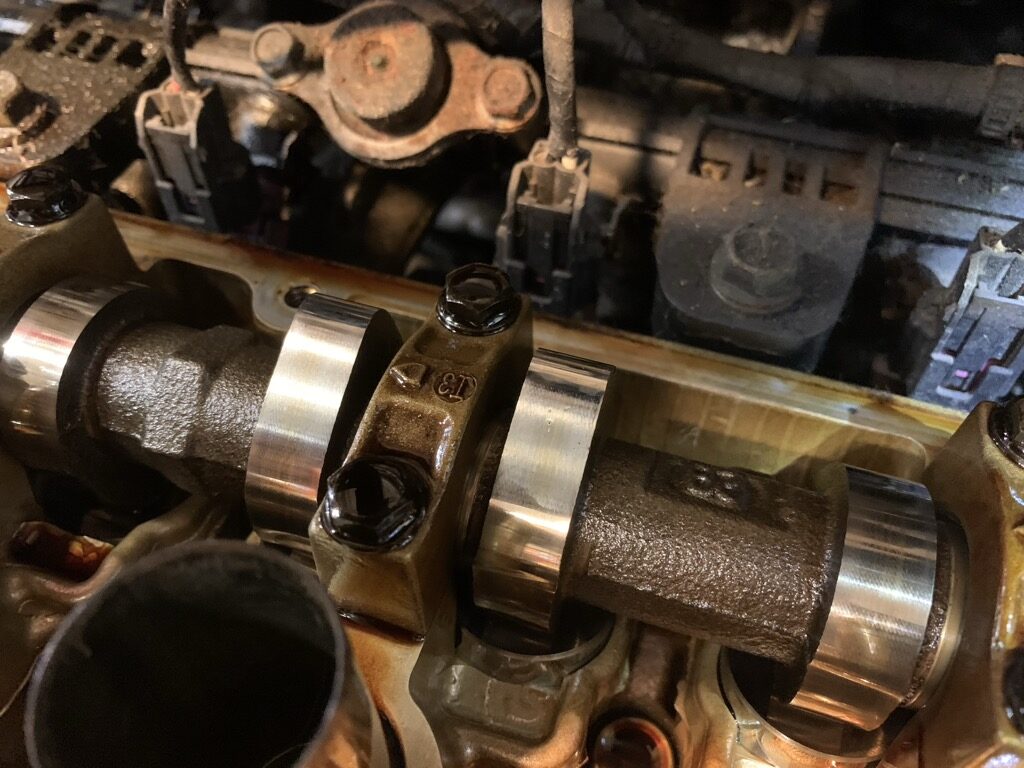

One thought bounces back and forth as I’m attempting not to dwell on it: dead. Past year took away a couple of people. One of them was my good neighbour. Every time I walk by or look out of the window, somehow I expect to see him driving by in his lovely Audi, stopping to say “what’s going on?” or blow leaves onto my property, later saying something like: “I’m getting old… it’s getting hard to take care of things…”. I always imagined myself being somewhat resistant to … loss. While I can stand around a funeral emotionless and stare at people with a poker face, inside things boil unstoppably, quietly blowing past seals, valves, and leaking out in the form of deep uncontrollable sadness.

I guess lucky people pass away fast, but some end up in pain for a while before the inevitable. I think of my aunt who suffered through, and my neighbour. We don’t just stop one day (at least most of us) – we get sick, bit by bit bodies deteriorate. A while back my cousin asked: “why didn’t they go to a doctor if there was a pain” – I assumed it was rhetorical. But I will answer, if not to him, then to myself: because deterioration is gradual. Bodies fall apart slowly, giving us time to adapt to new realities and to deal with it as much as we’re able to – physically and psychologically. As time goes on more and more family and friends will succumb to health issues… and unfortunately a few did this past year. Some had life-changing issues, others… well, let’s hope less so.

Over the last few years, I began contemplating life and choices. In some ways, there are very few choices for a particular person to choose from. I don’t want to go deep into the subject partly because it is a long conversation, partly because I’m nowhere near the end of the contemplation, and partly because today is not the day. However the idea is floating at the top of my waves and so I must proceed at least for a bit. I see the whole choice thing not as random crossroads where you choose to turn left or right, but rather as a recalculated decision that has already been made. It’s like going to a grocery store with a budget. Budget is already calculated, so you buy chicken at a certain price range. Yes, you can buy fancy chicken at a higher price but that will impact other choices by the end of the month or at a later point. So you have a range of decision-making: if there are a few choices in the range then perhaps you can choose, otherwise the decision is already made, you just follow it. Perhaps the grocery store example is too simple, but it illustrates my thought, and in life there are tons of parameters that affect which choices we make and which we just follow. I’m not entirely sure if the level of technology gives us more choices or less. On one hand, as we can calculate more and more, we see less and less randomness, which means more predetermined choices. On the other hand perhaps we can choose better at a point that actually matters. Last but not least is entropy that’s still with us. No matter how much we plan and calculate, some random factor can still throw a monkey wrench into our predictions – which makes life… well, for lack of a better word: interesting.

It’s been 4 years now and the war in Ukraine keeps going. I believe this year has been pivotal not only for Ukraine but also for me. As I learned more and more, my past ideas (and idealism) started to break down, eroding the foundation of my understanding of the world. I’m slowly leaving behind some of my naive ideas of “world peace and love” in favour of cold pragmatism. Don’t get me wrong, I still hope that there is a way that we can all get along… but it is just a hope that one day we’ll get there. The pragmatist in me sees that day as a “not so soon” prospect locked behind technological advancements and humans going to space. But back to the present: it is stunning and inspiring to see how Ukraine fights and operates despite all the challenges.

I hope 2026 is going to be the last year of the war. I believe Ukraine will hold out and win. Odds have been against Ukraine, but despite that it managed to achieve so much in so little time with such limited resources. It is truly astonishing. People will be studying the war for decades to come. Slava Ukraini.