Unit testing, as important as it is, is still treated as an afterthought. First, we write production code and then tests — if we have enough time and, more importantly, the will. Unfortunately, the natural result of this process is missing coverage, weak or absent assertions, and, more importantly, a lack of real exercise of the production code. I believe these issues are well known, but somehow they’re still not important enough to change the process. After all, we have production code; let’s ship it — “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”

In my opinion, this issue is well addressed by Kent Beck and Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob), who emphasize starting with a test. Unfortunately there seems to be lots of fluff, buzz and general misunderstanding of TDD. No, it is not Test-First. No, there is no magic sauce. No, there is no need to read tons of books or go to fancy lectures. After reading a few books, watching a few videos, attending a few fancy lectures and a few years of relentless practice, I can definitely say that all you essentially need is to read Kent Beck’s book – Test-Driven Development: By Example, watch Robert C. Martin and stick to The Three Rules of TDD. While Kent and Robert do not address every single scenario and issue, the above resources are more than enough to extrapolate and adapt the technique, let’s say to microservice architecture (which is not originally addressed). Now I’m not saying those are all the resources that you will ever need, but those are essential for TDD! Last but not least, if you don’t know how to do dependency injection without @Autowire (unfortunately I’ve seen that), it does not mean TDD sucks, it means you lack knowledge. TDD is not magic or a Swiss Army knife, it is a specialized technique for writing code independent of any specific platform, framework or language.

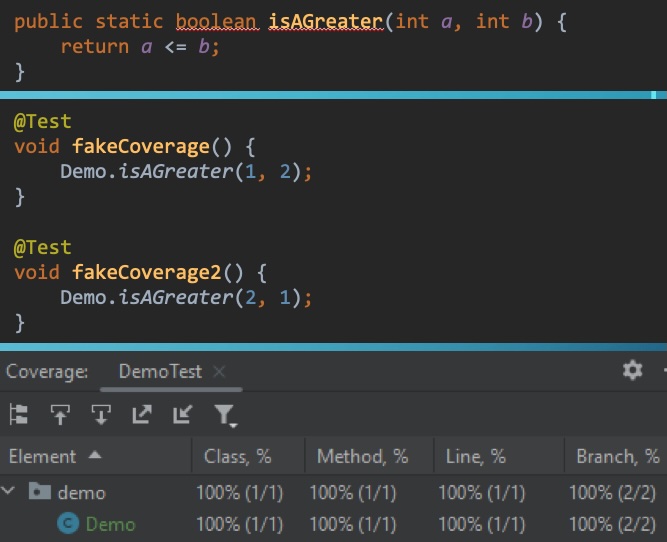

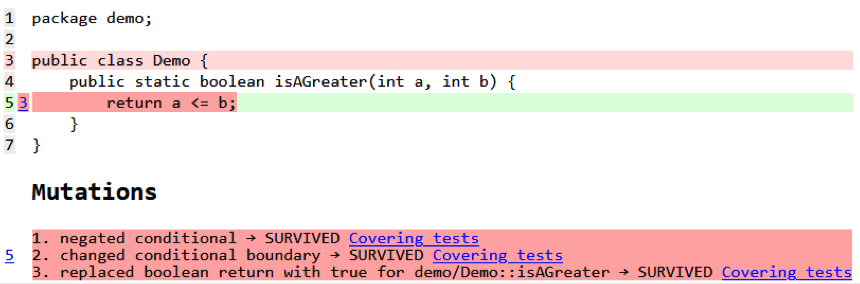

Unfortunately TDD is not widely adopted, and even if it was, we are still subject to mistakes — we are only human. Under these conditions we need a solution that does not rely on a human. One bad solution is code coverage. Code coverage has been around forever and is loved by managers as it neatly translates to charts, means little, and can easily be faked by developers. Code coverage has its uses, but it is useless in determining how well production code is actually tested. But don’t despair, we do have a solution — mutation testing. Mutation testing has a simple premise: change production code, see if any tests fail. If nothing is failing after the change, that means insufficient testing. In an inverted way it sure resembles TDD. While the premise is simple, execution is quite expensive! See how long your test set takes, then see how many logical and state changes can be applied in production code, multiply those numbers and you see how much time mutation testing will take — in short, a while for a sufficiently large project. That is probably the reason we don’t see mutation testing everywhere.

Fortunately the Java world is blessed with a modern tool for mutation testing – PiTest. It provides lots of features in its open source form. Even more features come with the commercial extensions, which integrate into a modern pipeline (or dev machine) and provide quick feedback to developers waiting for code review on their code changes. I wholeheartedly suggest buying a license and using the full power of mutation testing if code quality is important. Unfortunately my company, for various reasons, isn’t quick to sign up, despite claims to strive for quality. After a proof of concept, presentations, near begging and a final rejection, I fell into depression. I really wanted to use PiTest for tangible results and partly because it would have made my life a lot easier and the life of junior developers a lot harder – since I would not have to spend any time figuring out if their test code actually tested enough or anything at all (yeap, I’ve seen those cases too).

Finally, I realized I’m an engineer; my realm of possibilities lies far beyond microservices. I decided to build a “Poor Man’s PiTest”: a small tool that takes the open-source core and combines it with the power of Bash, Git, and a few other Linux commands. That gave me the ability to build only the projects that are needed, run PiTest only on the changed classes in a multi-module Maven project with a mix of JUnit 4 and JUnit 5 modules, perform timing analysis, log everything for debugging purposes, and optionally skip builds and/or focus on a single module if needed. So far it works well and, let me tell you, junior developers just “love it” — especially when I give them a long report of everything that’s been missed.

I figured someone might be in a similar situation, perhaps needs a bit of inspiration or an example, so I created a GitHub repository to share the script.

Thank you, and I hope the script will be of some use.