Over last nearly three months we’ve been hosting refugees. Perhaps it is a noble cause, may be admirable but we did it because it seemed as the right thing to do – people needed help and I and my wife were in a good position to help. I believe it is the biggest selfless act we performed to date. But I’m not writing this to brag, I’m writing this because I’m deeply sad and somewhat mentally struggling to process the past three months.

Let me start by stating somewhat fascinating (at least to me) fact; in the last three months, I learned nearly nothing about these people. All the time it felt like they didn’t want to be bothered. After initial few of attempts by me and my wife, we frankly gave up. It felt like they were ignoring us as much as possible. Most of the time we walked into a common area, they would leave (even though we encouraged the use of common area). Efforts to socialize were made but ultimately failed. We still talked but mostly when they needed something: taking to places, food, documents, resume and stuff like that. Granted, our family is having hard time with traditional breakfast/lunch/dinner – we simply don’t have “get together and eat”. But once in a while we do, at one point we got together for Chinese food dinner and invited the refugees. Kids (age 8 & 12) didn’t bother joining and their mom joined but the conversation didn’t really take off, as soon as food was done she left to her room and closed the door.

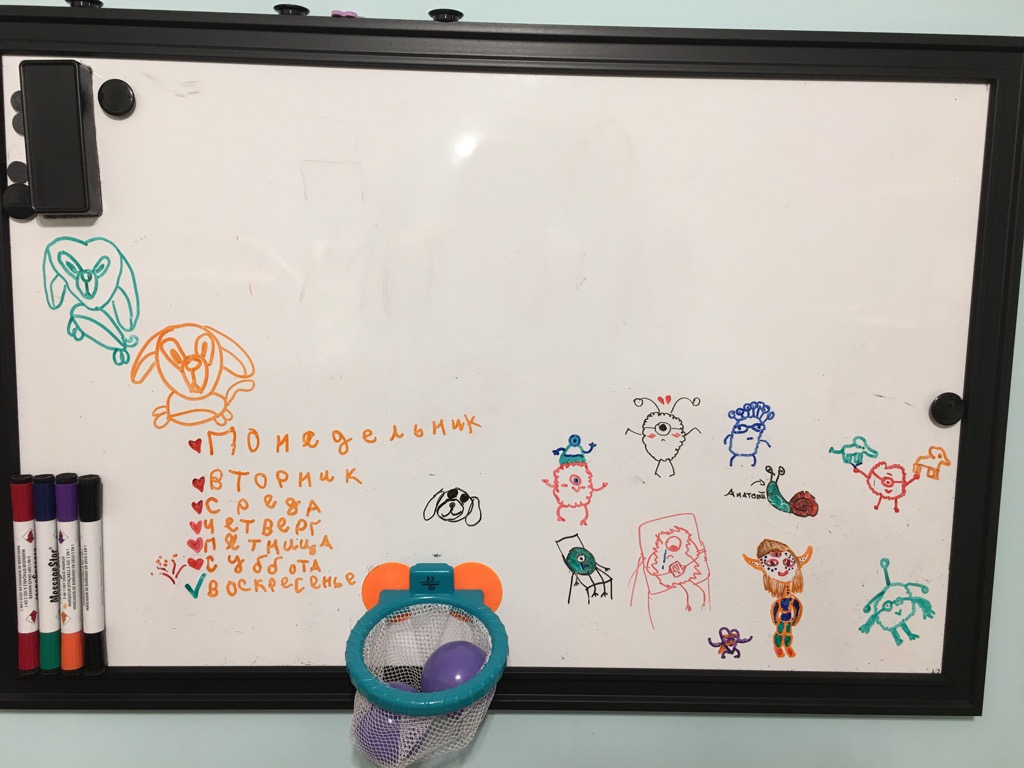

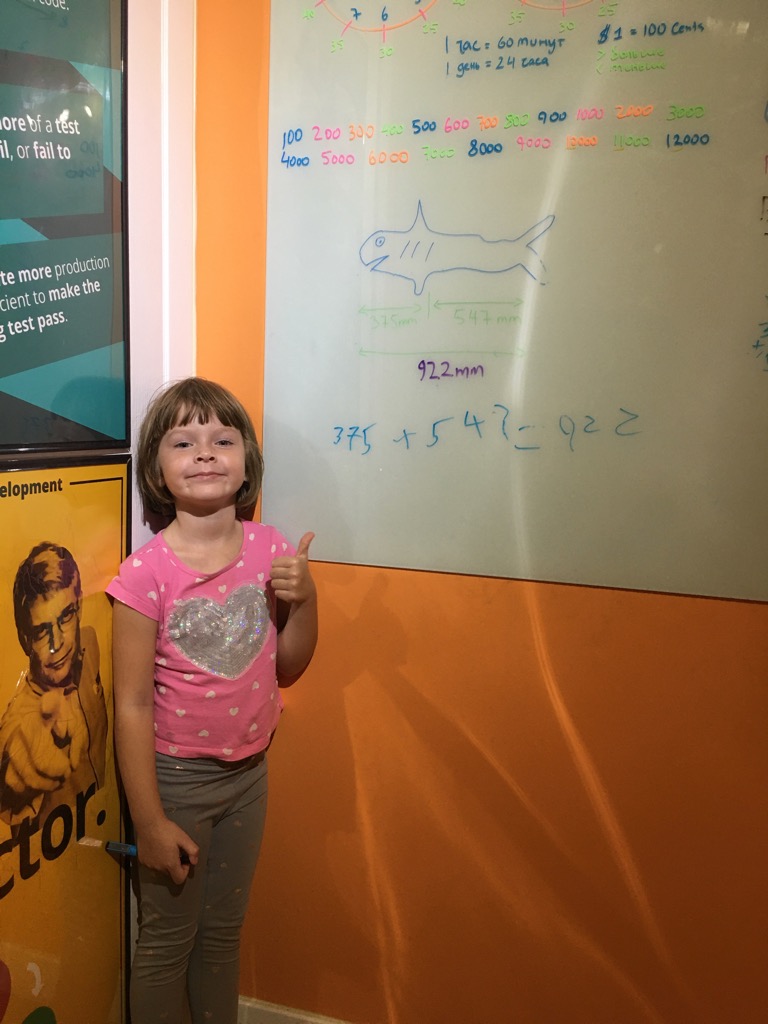

The kids are fascinating, simply because I never encountered such behaviour before. They never said “good morning”, unless I said “good morning” to them first. Forget about “good night”, may be “thank you” couple of times. I never met such a shy/private kids before. I remember meeting a super geeky boy a while back, but even though he was super shy, he still seemed pretty happy to be noticed and talked to. In this case kids seemed to regard me as necessary evil (at least that’s the way I felt), unhappy about any conversation attempts and never wanting anything. I never met any less curious kids in my entire life. Whenever I attempted to offer anything, they would immediately say “no”, in some cases even before I managed to finish a sentence. I have a six year old and it seems she received exactly the same treatment after initial several days of hanging out with the refugees. I know older kids don’t always like to hanging out with younger ones. But total ignore? It was painful and somewhat fascinating to watch my kid, she seemed to figure it out on her own and after sometime didn’t even notice the refugees.

I don’t know if we offended them in any way, I keep thinking about it but it’s not like we had extended conversations or discussions about anything. Most of the time they just stayed in their room, the door closed and didn’t communicate with us. We helped as much as we could – as much as I wish my family had received in a similar situation. We bought their airplane tickets, beds, food, clothing (some used, some brand new), helped with paperwork, provided a car to practice driving, pickup from the airport (which is 4 hours away), introduced to some people we knew and my mom somehow managed to get summer camp for the kids free of charge (typically about $300 per week per kid) – thank you city hall! Yet as time rolled on, we all got a feeling that we were bothering them, my wife mentioned that we were given the “cold shoulder”.

After nearly three months, one day, as I was making a tea in the kitchen, the refugee lady came out of the room and told me that she needs help – a ride to Brampton. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to spend my weekend driving refugees 4 hours away and then returning home. Despite advice of everyone (who knew what’s happening), I decided to drive the refugees to Brampton, to make sure they got from my place to their destination safely. As the day of departure approached, I was tensing up, I thought to myself: surely, the refugees will at the very least come out the room and say “thank you” and “goodbye”. I didn’t expect a dinner or tea or cookies, I mean after spending so much time avoiding us, I really didn’t expect much, no hugs, just a simple old “thank you”. My wife chuckled at me and gave me a new name: “Eugenius Simpletonius Maximus”, implying that I’m kindly naive. My mom simply said: “you will receive no gratitude”. Friend of mine said: “she will not thank you” and added that I’m hopeless optimist, yet, I still believed in basic human gratitude. The final evening came and went, my mom received no thanks even though both of them were home all day long. Me and my wife came home in the evening, the door remained shut with light inside – no thanks or goodbye came to us either. I got deeply upset.

Early morning the refugee lady asked for help – to take luggage to the car. So I did, I had a nut in my stomach, I briefly considered driving them to the nearest train station and leaving them there, but decided against it. So we drove for 4 hours towards destination in complete and utter silence. I still could not believe what had happened and I definitely didn’t know what to say, I was in complete and utter shock, the lady made no attempt to talk to me or even look at me the whole drive. The final moments were memorable, as we arrived, I unloaded the car, looked at the lady – she was busy with her kids, I walked to the car, looked at her again, she was still not looking at me, I sat into the car, still no attention to me, I started the engine – she didn’t even turn around and I drove off. I didn’t wait around, figuring everyone else was right at the end of the day and I was dead wrong.

45 minutes after I drove off, the lady decided to send “thank you” emails to my mom and to my wife, an email, after nearly three month of stay and all the help, we got an email! At this point I didn’t argue with my wife when she said “she is not done with us, she needs something from us” and she was dead right once again.

P.S: I’m still deeply upset, I know it will pass… but I’m still having a hard time comprehending the last three months.